One within Heaven and Earth: Revisiting Lao Jia’s Oeuvre

2016-12-09 15:13:57来源:作者:Wang Luxiang

Over thirty years ago I wrote an essay entitled Abandoning Form and Exalting Shadows, marking the start of my interpretation of Lao Jia’s work. Over thirty years later, as I revisit Lao Jia’s work, I find myself crouched over my drafts with my thoughts ambling between heaven and earth. In his work I encounter a feeling that is at times evocative of the natural expansiveness of Zhuangzi while at times his work roils with the moral rectitude of Mencius’ philosophy. In Lao Jia’s painting one finds the pulsing energy of the universe and the strength of thunder and lightening.

Lao Jia is famous for his freehand ink paintings of horse, riders and grasslands, and it is easy for many critics to focus on these surface characteristics. When I wrote about Lao Jia thirty years ago, I also fell into the same trap of microcosmic interpretation, merely discussing the form and use of ink that I saw before me. However, when I saw his personal exhibition at the National Art Museum of China and read the survey published by the People’s Fine Arts Publishing House entitled Modern Chinese Masters: Jia Haoyi, suddenly I understood the vastness of the cosmos. Horses, riders and grasslands all disappeared within the totality of heaven and earth, leaving behind only ephemeral ink shadows!

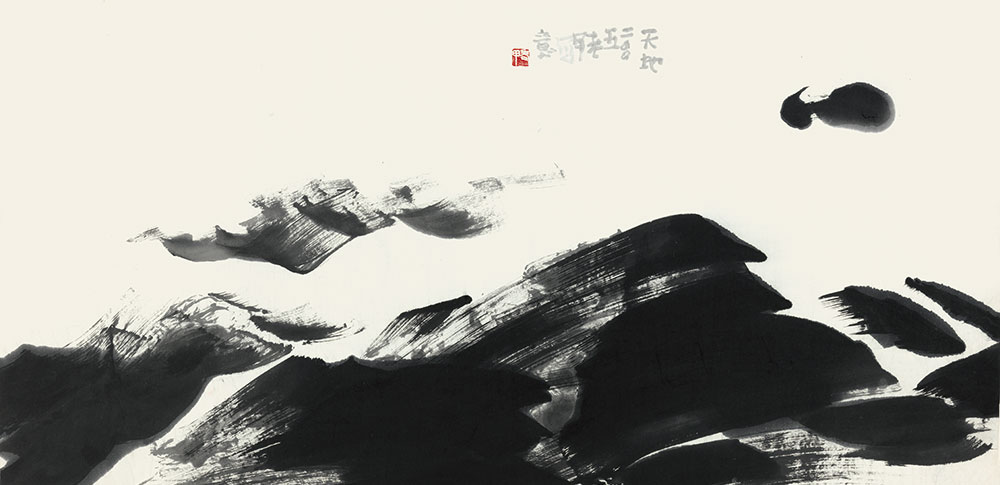

Between 1995 and 1997, Lao Jia created a series of ink paintings entitled Sky and Earth Are One, including works individually titled Universe, Sun, Shadows, Moon, Dusk and Changes. Imbued with elements of abstract composition and defined by both bold, sweeping brushstrokes and weighty, vigorous use of ink, the Sky and Earth Art One Series constructed a visual portrait of the cosmos never before seen in Chinese painting that was at once all-encompassing, vast and mysterious.

Such an impression was my entry point into Lao Jia’s spiritual world and artistic landscape.

Lao Jia is a painter with a philosophical understanding of “ultimate concerns.” This is very rare quality amongst Chinese painters. Influenced by both traditional Chinese culture which is both pragmatic and rational, and the ideology of contemporary Chinese education, most Chinese artists lack an understanding of “ultimate concerns.”Although they abound in historical consciousness and political opportunism, they completely lack universal consciousness and transcendental ability to surpass the material and behold the glory of the heavens. Lao Jia, however, is an exception. By the 1980s Lao Jia had completed a series of ink paintings entitled In the Beginning, in which we can clearly remember the following image: red clouds floating in a clear sky with a fine line of ink marking the horizon where heaven and earth meet; several drops of thick ink mark the bare body of a small child, standing in between heaven and earth and gazing upon the water ditch in which he just pissed, lost in deep thought. According to the “three talents” of Chinese philosophy, heaven and earth give birth to the universe, while man is in the center, connecting heaven and earth. These “three talents”—heaven, earth and man—enable the beginning of culture and the birth of consciousness. In the Beginning thus depicts the earliest ancestor of human thought and consciousness: his confusion has continued up until today. However, it is precisely such meditation and transcendence, indifferent to hunger, thirst or survival, that allowed man to evolve past animals and become the creator of civilizations that pine towards the heavens. Through the use of several extremely simple symbols, Lao Jia has depicted the poetic and childlike moment in which human civilizations were established. In the words of Marx, this is the beginning of the entirety of human philosophical history.

“When perched between heaven and earth do I think of the ancients/I stand alone in the vastness and recite verses to myself.” This is a poem by Du Fu. The state of humanity is to be perched between heaven and earth, and this state is inclined to towards two states of parallel existence. When Lao Jia paints horses and bulls, in reality they are both reflections of spiritual imagination, or self-portraits of humanity. Just as figure painting includes both individual and group portraiture as well as great historical spaces, Lao Jia’s horses and bulls also have individual and group portraiture as well as great historical spaces, expressing Lao Jia’s meditation on the destiny of humanity as well as his aesthetic ideals in respect to the spirit of heaven and earth. Through the repeated representation of these two animals that he so loves, Lao Jia has expressed a limitless yearning for force, speed, freedom and peace.

Under Lao Jia’s brush, horses become symbols of speed as well as symbols of the soul and winds of freedom. He uses what seems like electrically charged ink and brush to capture passion we feel when inspired by the speed of the spirit of heaven and earth to a level that has no historical precedent. No famous painter of horses in either Western or Chinese traditions has been able to so truly and expressively capture the speed of horses and their ephemeral beauty. Speed is in fact the best expression of freedom, leaving behind everything else in a pile of dust. Within the central values of humanity, the first value is freedom. The pursuit of freedom, the guarantee of freedom and the realization of freedom has shaped the eternal destiny of humanity. The reason why Lao Jia’s galloping horses excite me and inspire passion in my soul time after time is not only due to the visual sensation I receive when looking at the work’s physical brushstrokes, but also due to the spirit of freedom that lies behind the artist’s brushstrokes and imagination—at once patently romantic and full of both ideals and passion. Who would not like to incarnate such a free spirit?

Interestingly enough, the first hexagram in China’s most ancient work of classical philosophy, the Book of Changes, lauded as the sum of Oriental wisdom, is qian, or the Creative. The Creative is heaven, and thus is also a horse. The Creative represents the movement of the universe: “The movement of heaven is full of power. Thus the superior man makes himself strong and untiring.” This is to say that the universe moves with great speed and quickness, and that mankind should follow the rhythm of heaven’s movement. Lao Jia has selected a representation of heaven and the Creative: horses. Horses are heaven, and are also the Creative; they represent strength, speed, freedom and the perennial raw power that ripples through the universe.

Bulls, represent thus the Receptive in relation to the Creative. The Receptive represents the earth, and is firm, steady, strong and inclusive. This is another type of great strength and spirit; without the existence of the Receptive, the speed of the Creative would become a destructive force, and without any forbearing presence, the freedom of the Creative would become unbearably inconsequential. “The earth’s condition is receptive devotion; thus the superior man who has breadth of character carries the outer world.” The commentaries on the Receptive tell us that freedom with responsibility and endeavor is positive freedom, while the earth and bulls are the representation of such virtue. Ink bulls as painted by Lao Jia when understood in contrast with his horses create the duality of the Creative and Receptive; the earth holds all the virtue of the Receptive and the bulls in his painting represent all the firmness of the ground while being as towering as great mountains.

I have noticed that when Lao Jia paints horses, bulls or figures, he likes to use thick ink to represent form within a backlit environment, while also employing a looking-up perspective. Such treatment of the pictorial space not only renders forms within simple and generalized, but also inspires an elevated feeling of the sublime, with dark cut-out shadows mysteriously retreating into the depths and strong black and white contrasts creating a subjective form that evokes the totality of sculpture. Simultaneously, the changes of ink within the contours of form appear supremely rich, employing techniques such as accumulated ink, splattered ink, broken ink and flying brush to express the beauty of Chinese ink to supreme levels. In regard to the relationship between form and ink, Lao Jia has thoroughly understood the contradiction between abstract geometrical form and the charm of ink and brush, and all while taking the freehand form of Chinese ink painting and bringing it within the context of modern composition and form, Lao Jia has not destroyed the charm of Chinese ink panting, but rather expanded its mysterious Oriental charm, following within the efforts of Mr. Li Keran and marching bracingly towards Chinese ink painting’s modernity.

I mention Li Keran because I have noticed that Lao Jia’s efforts in the realm of ink painting can be connected to the oeuvre of Li Keran.

Simply comparing Lao Jia and Li Keran, both have similar characteristics: both like painting bulls, both like heavy use of ink, both err towards the use of angular representation and avoid circular forms in representation, both attempt to bring the firmness and weightiness of sculpture within ink painting, both enjoy using backlighting and both exalt in depicting the quixotic vastness of twilight.

Of course, with respect to the modernity of ink painting, Lao Jia has advanced farther and with greater freedom than his predecessors, especially in his use of angular brushes to splash ink and the broken brush to depict the shape and posture of his subject. Lao Jia not only possesses the virtue Li Keran described by saying “greatness is daring,” but also manifests what is called “the essentiality of the soul.

“Daring” can be understood as Lao Jia having reached the apogee of representative painting, which can be understood as the frontier between representative and abstract painting, thus allowing ink and brush to break free from the restrictions of representation, achieving the liberation of ink and brush. In this respect, Lao Jia has achieved the zenith of Oriental imaginative painting: if he were to go any farther, his work would be abstraction. However, this final element of self-restraint allows us to see the difficulty within Lao Jia’s artistic practice: with an unflappable spiritual clarity and lucidity, Lao Jia allows every dot, every line and every surface to possess the figurative order and logic of representative painting in what appears to be the unbridled and arbitrary expression of ink; while indulging in the song of ink and the dance of the brush, Lao Jia never forgets that form and imagination must be concretely realized on paper. Thus, Lao Jia devotes equal consideration to representation and abstraction—two differing types of thinking and ability. It is very difficult for an artist to manifest both of these diametrical opposites, and Lao Jia has succeeded in achieving a supreme equilibrium between the two—this is far from simple. In fact, a Chinese freehand ink painter should possess such an balancing ability. If he does not possess this ability, then it is impossible to become a master. Qi Baishi, Fu Baoshi, Pan Tianshou and Li Keran all possessed the balancing ability to walk on the tight-rope between resemblance and dissimilitude. “Greatness is daring” means that an artist dares to act, ceaselessly exploring the limit between representation and abstraction; “the essentiality of the soul” means that he has found such a limit, achieving a “balance of terror.”

Lao Jia also occasionally paints flowers and plants as well as some other charming subjects, but under his brush these images also become reflections of the “oneness of heaven and earth.” Thus, for a great freehand painter like Lao Jia, everything between heaven and earth possesses independent vastness—everything possesses the potentiality of both the Creative and the Receptive. Heaven and earth were created through the transformation of the Creative and the Receptive, and mankind is perched in between, basking in the sumptuousness of the cosmos, alternating between bulls and horses, one moment incarnating a celestial steed galloping across the sky, one moment incarnating a strong bull bearing a heavy weight, pursuing freedom while bearing endless responsibility—sometimes achieving the heavens, sometimes loosing the earth, sometimes recumbent on the earth and unable to behold the stars. This is the state or perhaps the destiny of man, and it is this destiny that brings us towards the vastness of the spirit, standing alone moaning within the expansiveness of the cosmos: this is the poetry of mankind. The ultimate concerns of art are perhaps thus.

Can’t all of Lao Jia’s efforts be seen as struggling towards the achievement of the “balance of terror,” the tension-filled expression of the Creative and the Receptive, the horse and the bull, heaven and earth?

One within heaven and earth, the Creative, Receptive, horse and bull—tension will always exist within the universe. It is this tension that allows the generation and constant rebirth of primordial energy. Lao Jia aims exactly to express the primordial energy that ripples between heaven and earth.

As I revisit Lao Jia’s oeuvre, I came to these conclusions. As for Lao Jia, we can only ask him if he finds truth in what I see.