Qi and the Way of the Creative: On Lao Jia's Painting

2016-11-04 14:30:27来源:作者:Chen Chuanxi

Art historians believe that the feeling a painting gives people is utterly unimportant, thinking that joy one receives while viewing the painting is important. I believe that what feeling a work of gives you, as well as what the painting makes you think of are both important, and sometimes the two are inseparable and mutually influencing.

When I view Lao Jia's painting, the feeling I get is not ordinary, and at the same time, his work makes me think of many things.

I vaguely remember an essay I once read but I can only remember the basic outline, which said that an official once said the following loudly during a banquet: "The wine is bad." The other guests surprisedly asked, "How is the wine bad?" He responded: "The wine has too much of a wine taste." Wine of course has wine taste, how could it be called bad? He gave long explanation, saying how good wine should have certain qualities, such as being mellow, dynamic, deep, flowing and soft, as well as fragrant, light, moist, and round. If wine has too much wine taste, then the real quality of the wine is concealed. I personally do not drink so I cannot say much on the subject of wine, but I have some knowledge of jade, and I know that jade is not just another type of rock. The reason jade is precious is because jade possesses the qualities of the Confucian gentleman. In Shuowen it is said that jade has "five virtues", and in the Book of Rites it is said that jade has "nine virtues": "The gentleman compares virtue to jade; it is mild and yet has luster, like benevolence; it is compact, meticulous and grainy, like wisdom; it is purely honest but does not hurt, like justice; it weighs down as if it was hanged, like the rites; if you knock it, its sound is light, and is embarrassed if the sound is too long, like music; its flaws do not cover its marks, and its marks do not cover its flaws, like loyalty...." Ordinary stones, called min, resemble jade, but: "the gentleman values jade and does not value min." This is because min does not possess the "nine virtues." It thus appears that the reason jade is valued is not because of the jade itself, but rather because one can see the qualities of a "gentleman" in jade.

Painting is also thus; so what is painting? The Guangya states: "Painting is grouping objects." The Erya states: "Painting is giving form." The Shiming states: "Painting is propping up; using color to prop up phenomena." Which is to say that painting must group objects, it must give form, and it must have color. However, the reason good paintings are valuable is not because of the paintings themselves, but because they reflect some type of spiritual meaning. The great Ming dynasty painter Dong Qichang strived to reflect Zen within painting, and his painting studio was called the "Zen Chamber." His student, late Ming dynasty Zen master and monk Dandang was even more astonishing: his painting didn't group objects, did not seek form, and did not even have color. His paintings are like someone who does not need to pay attention to the particularity of phenomena, able to seize their essence; it does not matter what it is, as long as the essence is captured, it is a successful painting. Within Dandang's painting, although we see form and color without seeing form and color, and his images possess an atmosphere of "emptiness, coldness, silence, and purity", a deep expression of Zen. In his commentary to his own painting, he stated: "As if one brushstroke is both a painting and not a painting; as if not one brushstroke is a painting and also not a painting." If we judge painting based upon grouping, form, and color, we find that his painting does not possess grouping, form, or color, and not one of his brushstrokes creates a painting; however if we hold that painting expresses something other grouping, form, and color, possessing something deeper, just as Dandang expresses his Zen philosophy through painting, which is to say that painting should be Zen itself, then every brushstroke has Zen meaning—the definition of a good painting. If we discuss Dandang's painting with such an understanding, then every brushstroke in his work is painting. This part is a bit philosophical, and we should invite a philosopher to explain it clearly. Now, for the moment, let us discuss painting; let us discuss Lao Jia's work.

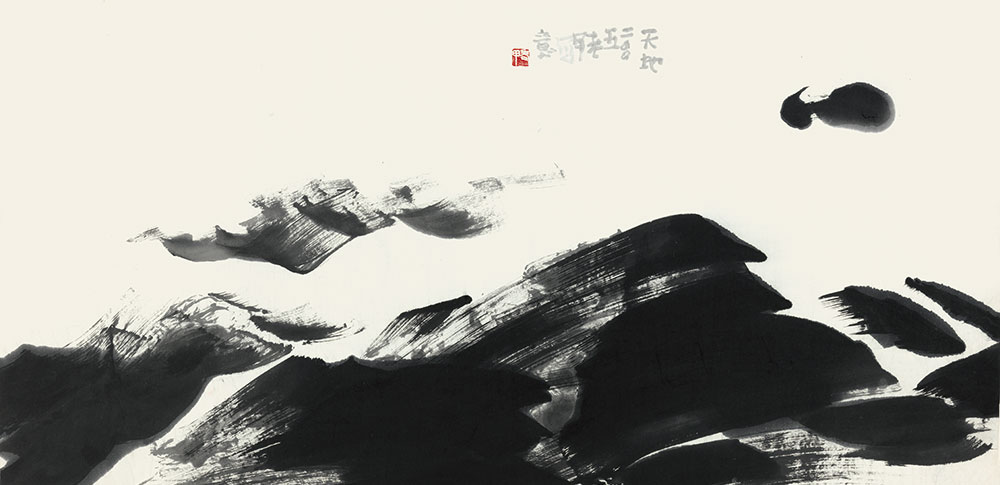

Lao Jia's painting can truly be described with the statement "as if one brushstroke is both a painting and not a painting." Such vigorous and dense dots of ink, splaying and splashing at one's will, flying and dancing madly, doing exactly as one pleases, disregarding all tradition and rules—is his painting grouping? Is it form? Does it use color to prop up phenomena? It is neither of these things. Thus, some people say that the concept of one brushstroke being a painting is a spirituality, some people say it is a philosophy, or a completely new aesthetic concept used to explain the deep essence of meaning within Chinese culture—all are true. If we say that spirituality, philosophy, or an aesthetic concept can all be the expression of a painting, that is to say that painting is the elevation of spirituality, philosophy, and aesthetic concepts, then his painting is as if one brushstroke is a painting. One of the characteristics of Lao Jia's painting is that he absolutely does not use brush and ink to represent form, believing that doing as such is an extremely simple endeavor. He does not have any regard for making paintings just to represent form. His form is employed in the service of his brush and and ink, with his brush and ink expressing his individuality, expressing his style, energy, and character, representing a expansively generous vitality and righteousness. As the world of painting is filled with paintings of a feminine and delicate style, Lao Jia's paintings are especially precious as they sweep away the listless and fragile paintings omnipresent today, giving a shock to the spirit, making people know that Chinese painting, in addition to being delicate and elegant, can also be an expansive and exciting art.

Ever since the Ming and Qing dynasties, due to the individual effeminacy of several southern literati, silence, purity, and scholarliness in art have been advocated. Of course, silence, purity, and scholarliness in painting are very nice, but this cannot be the only standard; virility, expansiveness, masculinity, and fullness are also important. However, these qualities were denigrated by southern literati as vulgar, artisan, and full of bad habits. Thus, the personalities of many painters were suppressed, and many different styles were repressed. In an article entitled "On Virility and Expansiveness" (published in Meishu, June, 1992), I analyzed the dangers for our people present in this trend.

In reality, truly scholarly paintings are very few, with the majority of painters imitating the surface of scholarliness, painting meticulously and minutely, not daring to use force with their paintbrushes, not expressing themselves, being rather a theoretical model, distorting things beyond recognition, making the world of painting full of emptiness and artifice. This trend pervaded all the way up to modern times, until a group of revolutionary painters such as Wu Changshuo, Huang Binhong, and Fu Baoshi appeared, giving a breath of fresh air to Chinese painting. Such a breath of fresh air was precisely the vulgar, artisan, and full of bad habits painting reviled by Ming and Qing dynasty literati. However, due to a weak personal temperament, the next generation of painters that received the previous generation's influence, resembled their predecessors only in appearance, and as a result messily splashed and sloshed, appearing strong and vigorous, but in reality empty and weak, not giving any satisfaction to the viewer. Thus, a group of painters turned to Western painting, attempting to use the visual methods of Western painting to replace those of Chinese paintings. However, Chinese painting is based upon the foundations of Chinese culture, and Western painting is based upon the foundations of Western painting. Any attempt to transplant the forms and essence of Western painting into that of Chinese painting to good effect is extremely difficult. Thus, many advocated a revival of tradition. Tradition has always been very strong, given that this effeminate and fragile style has been popular in China for several hundred years, and revival thus implied a rival of such delicate and fragile painting. Especially for painters from the Yangtze river delta, due to their natural disposition, they both intentionally and unintentionally revived this tradition of delicateness. Although novel for a period of time, Chinese painters across the nation imitated this new trend, leading to the proliferation of such gentle painting, with painters believing that this was the only way to be traditional. Lao Jia's painting also appeared during this time, possessing a great force. His paintings are not an imitation of tradition, ignoring the rules of indirectness, reservation, softness, and restraint demanded by the ancients; on the contrary, he pursues the opposite. His paintings are explosive. They are both internally and externally strong, with brush and ink impacting directly, completely indifferent to reservation and softness, sometimes dry and brittle, reflecting a fierce spirit, called by some "true large xieyi". If we seek modern language within painting, there is modern language, something the ancients never had. Do his paintings Bate'er, Happy Muslims, Out to Pasture, and Galloping represent people or horses? It appears thus and it also does not appear thus; however, everything seems like a momentary torrent. Qi Baishi once wrote a commentary to his own painting saying, "Provoking without sound." Lao Jia's paintings roar, with works such as Wave Shadows, Morning Sunlight, and Streams of Iron all resembling horses, mountains, and wind, with the vague impression of ten thousand horses seemingly galloping wildly within an ambiance of flying ink and a tumult, while also appearing to not have a single horse at all. The artist uses the methods of modern abstract painting, while not being completely abstract, with not one brushstroke being a painting, and every brushstroke being a painting, creating a type of painting never seen before both in China and abroad, both in ancient and modern times.

A European philosopher that researches genius has written that the mind of a genius constantly reflects on a certain issues, and can completely imagine the beginning and end of a question. Smart people are also thus. The reason Picasso's style constantly changed was because he was constantly thinking of one style after another. Average painters are never able to conceive of a personal style, and thus can only copy others. Even extremely stupid painters know that they must create their own style, but they cannot think of anything new, and thus their brush has nothing to start from. Thus, Yuan dynasty writer Liu Shao wrote in the opening to the Renwuzhi: "The sages find intelligence the most beautiful." He also added that: "In seeing the level of someone's intelligence, we can know what he is capable of." We can turn the saying around by saying that we can know how intelligent someone is by seeing what he is capable of. Lao Jia's painting is constantly changing. In his youth he painted storybooks, painted extremely minutely detailed New Year's paintings, and later painted xieyi, large xieyi, and truly large xieyi. He already knows how he should change, and he "randomly ponders" every day, constantly thinking about endless possibilities. Once he has made achievements in painting figures, horses, and bulls, he moves on, trying something else. When painting horses and bulls, he mostly uses a very concise background, with some paintings not having a background at all. When he paints landscapes, he tries to fill the world up, with fullness as a characteristic. His landscape paintings are not only paintings of landscapes, but rather using landscapes as a medium in order to express his brush and ink. He still splashes up and down, moving left and right, using brush and ink to express his strength and force. There are many who are able to play with brush and ink; such painters are easy to find. However, those who are able to express a special ambiance with brush and ink are very few. It's like using the same stone to make a stone lion: the stone lions in front of the Xi'an Tang dynasty tombs appear to be looking down at everything, like an emperor lording over the world, whereas the stone lions from the Qing dynasty in Tian'anmen Square seem to be as docile as a dog or a cat. The quality of the stones is the same, and the tools used are also the same, but the energy and qualities expressed are completely different. The qi and posture expressed by Lao Jia's landscape paintings are like those of the stone lions in front of the Tang dynasty tombs, possessing the gait of an emperor looking down upon the world, with a posture sweeping the sky, filled with the force of the universe. Viewing Lao Jia's paintings is like viewing what is not a painting within a painting, seeing force, qi, and posture, all enough to excite you and rile up your spirit. That is to say that Lao Jia's paintings are truly those in which each brushstroke is a painting and each brushstroke is not a painting. Painters both in the past and in the present are all willing to spend time on a certain subject, and only Lao Jia is not willing, saying in a letter: "Wait until this series of landscape paintings is a bit more evolved, and I will paint another series to further develop." He still wants to change, and already has new ideas, preparing a period of time and then starting to paint. Once he has a new idea, he of course paints according to the new ideas, but he doesn't know what the painting will be like; in any case it will not be like his current landscape paintings, and he will not revive previous horse and bull paintings. Now, he is in a hurry, with new ideas pushing forth in his mind, not allowing him to gain any peace, forcing him to paint them. Many painters do not know what to paint, not knowing what to paint to be different than the rest. This is just an issue of the painter's quality—having new ideas, having new impulses, even if not being completely original, is the standard by which an artist's ability to succeed or not is measured. A painter must use this standard in order to establish whether he is made for painting and being creative, or just made for following.

The Commentaries to the Sixty-four Hexagrams state: "That which creates images is the Creative; that which follows is the Receptive. Thus the Creative is focused in his silence, is forward in his movement, and is thus able to create vastly. The Receptive is submissive in her silence, and evasive in her movement, this is able to spread widely." That is to say that the Creative is original in its creation, and the Receptive is a follower. Anything requires both the creative and the follower; without creation, then there is nothing new, with creators being the limited few; if there is now following, then new things will not spread widely, and the force of original creation will not expand. Thus the Creative is masculine, and is hard, and the Receptive is feminine, and is soft. Lao Jia's paintings are masculine and virile while also being original, thus they belong to the Creative. Ever since the Ming and Qing dynasty, our art has mostly belonged to the Receptive, with the Zhe painters of the early Ming dynasty following the court painting of the Southern Song dynasty and the mid-Ming Wumen painters following the "four Yuan dynasty masters", whearas the "Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty" followed Dong Yuan and Ju Ran, and the later Songjiang painters followed in turn the Wumen painters. The "Four Wangs" of the early Qing dynasty imitated the Songjiang painters, and later painting of the Qing dynasty imitated the "Four Wangs". With "following being the Receptive", and the Receptive being feminine and soft, our art thus has had too much softness. If the feminine force is too strong then the masculine force declines. Up until today this pattern has not been able to change, with art being the reflection of a people's spirit. Yin and yang create together the Way, with the Creative and Receptive together creating the heavens. Thus, our art needs the Way of the "Creative", and urgently needs virility and creativity—it needs art like Lao Jia's.

After the appearance of Lao Jia's painting, there have been followers, which is natural. I am on the other hand worried about the followers being able to truly follow, because "that which follows is the Receptive", and the Receptive is not capable as being as virile and strong as the Creative. Lao Jia's paintings are not paintings, but rather an expense of force, the explosion of gesture; like the screaming of great wind, like the surging of the ocean's waves; like lightening awaking the universe, like thunder rumbling throughout mountain ranges. This is precisely the spirit our times need, this is the energy our nation needs. If such an energy is able to spread widely, then our times are fortunate, and our nation is fortunate as well.

I hope that art like that of Lao Jia's can become the mainstream of art; I hope that our people can have more virility and expansiveness, possessing more of the Way of the Creative.